Forensics brings new ways to fight counterinsurgency warfare

A relatively new weapon to combat the enemy is being used in Afghanistan and Southwest Asia. It's been around a little more than a decade and fits into the counterinsurgency warfare necessity of being able to identify who the enemy is by person versus just identifying an enemy organization. Jon Micheal Connor, U.S. Army Public Affairs, reports.

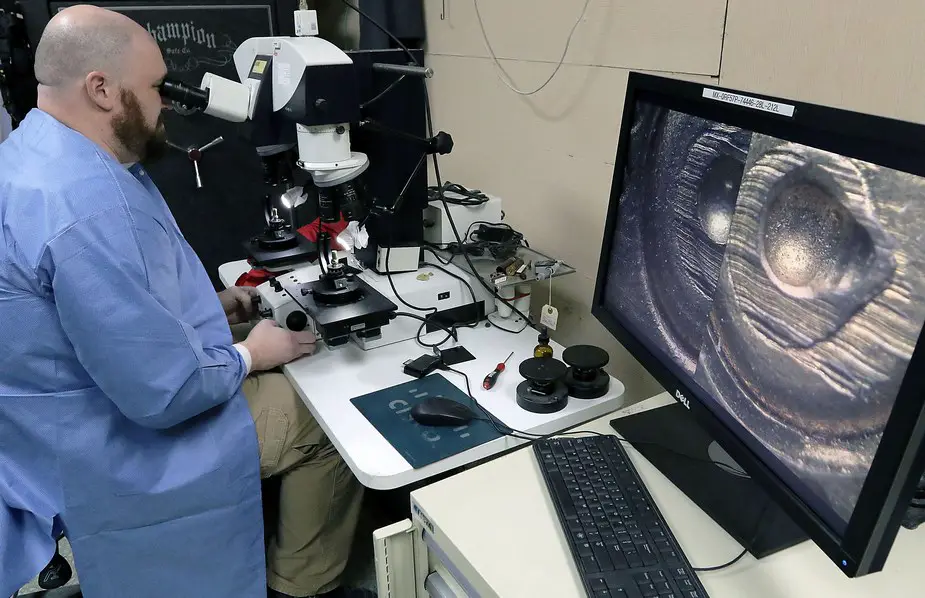

A firearms and toolmark examiner comparing cartridge cases on the Comparison Microscope. (Photo credit: Jon Micheal Connor, Army Public Affairs)

The Afghanistan Captured Material Exploitation Laboratory here is aiding combat commanders in their need to know who is building and setting off the enemy's choice weapon -- Improvised Explosive Devices. With this positive identification of enemy personnel, coalition units working within NATO's Resolute Support mission can then hunt down the enemy for detention or destroy if need be. "The commanders are starting to understand it more and seeing the capability and asset it provides," said Kim Perusse, incoming ACME lab manager at BAF. Perusse said commanders are embracing it and wanting more forensics exploitation.

Personnel from ACME deploy from the Forensic Exploitation Directorate which is part of the Defense Forensics Science Center located at the Gillem Enclave, Forest Park, Ga. DFSC also contains the U.S. Army Criminal Investigation Laboratory, and the Office of Quality Initiatives and Training.

The DFSC's mission is to provide full-service forensic support -- traditional, expeditionary, and reachback -- to Army and Department of Defense entities worldwide; to provide specialized forensic training and research capabilities; serve as executive agent for DoD Convicted Offender DNA Databasing Program; and to provide forensic support to other federal departments and agencies when appropriate, its website stated.

ACME provides forensic/technical intelligence, analysis, and exploitation of captured enemy material. The findings are then provided to coalition forces and the Afghan National Defense and Security Forces to counter the IED threat, attack the counterinsurgent networks, advise the Afghanistan government's exploitation labs, and provide prosecutorial support to the Afghan justice system, an ACME slide presentation stated.

ACME capabilities include latent print examination; explosive/drug chemistry; electronic engineering; explosive triage; DNA; firearm/toolmark analysis; weapons technical intelligence analysis; and, provide assistance to the Afghan Ministry of Interior, National Directorate of Security, and Afghan National Security Forces.

As part of employment with DFSC, FXD, personnel must deploy every 18 months to a deployed lab for six months, as there are currently two, one here and one in Kuwait.

The Forensic Exploitation Laboratory -- CENTCOM in Kuwait supports military operations in Iraq and Syria, and is located at Camp Arifjan.

ACME's primary mission "is to allow the commanders on the ground to understand who's within the battlespace," said Lateisha Tiller, outgoing ACME lab manager.

Whether this is people coming onto the coalition locations as part of employment or those building the IEDS, forensics exploitation results in positive identification of such individuals. "Our mission is to identify nefarious actors that are in the CJOA [Combined/Joint Operations Area] right now," Tiller said. "We don't want them putting IEDs in the road, and blowing up the road, blowing up the bridge. We want that type of activity to stop," Tiller said. " 'How do you stop it?' You identify who's doing it; identify the network of people who's doing it. Eliminate them from the battlespace" as evidence collected is then shared with military intelligence, she said. "It's never just one person; identify the network," she said. By taking people out, the network "eventually is going to dismantle itself."

"The secondary mission is the Rule of Law," Perusse said. "Helping get the information out to the Afghans to potentially prosecute those nefarious actors that we may identify" through biometrics, chemistry, firearms, and toolmarks.

The conclusive findings and evidence -- criminal activity analysis reports -- is then shared with the Afghan laboratories as they work to build a case against alleged personnel who could be tried in an Afghan court.

The reports are also shared with military intelligence -- U.S. and NATO -- and also sent to the Justice Center in Parwan to assist in the prosecution of the enemy. The JCIP is located in the Parwan Province where BAF is located too in east-central Afghanistan.

The justice center was a joint U.S.-Afghan project to establish Afghanistan's first national security court. Established in June 2010, the JCIP exists to ensure fair and impartial justice for those defendants alleged of committing national security crimes in the Afghan criminal justice system. Coalition forces provide technical assistance and operate in an advisory capacity.

The reports are accepted in the Afghans courts because the Afghans understand and trust the findings of ACME. "Building that alliance is absolutely part of the mission," Tiller said. "The lines of communication are definitely open."

Because of this fairly new application of forensics to counterinsurgency warfare, the Afghans initially didn't understand it, the lab managers said. "They didn't understand forensics. They didn't trust it," Perusse said. "Especially DNA, it was like magic to them."

But as she explained, the U.S. also took a long time to accept DNA as factual and evidential versus something like latent prints. Latent prints are impressions produced by the ridged skin, known as friction ridges, on human fingers, palms, and soles of the feet. Examiners analyze and compare latent prints to known prints of individuals in an effort to make identifications or exclusions, internet sources stated. "Latent prints you can visualize, DNA you can't," she said.

The application of forensics exploitation as part of the battle plan started in the latter years Operation Iraqi Freedom, the lab managers said. OIF began in March 2003 and lasted until December 2011. This type of warfare -- counterinsurgency -- required a determination of who -- by person -- was the enemy in an effort to combat their terrorist acts. "I think there was a point where the DOD realized that they weren't utilizing forensics to help with the fight," Tiller said.

The operations in Iraq and Afghanistan were not big units fighting other big units, with mass casualties, but much smaller units engaging each other with an enemy using more terrorist-like tactics of killing.

Forensics told you "who you were fighting. You kind of knew the person in a more intimate way," Tiller said, adding, it put a face on the enemy. Forensics exploitation goes hand-in-hand with counterinsurgency warfare, Perusse said. "They're (Taliban/ISIS) not organized like a foreign military were in the past" but instead have individuals and groups fighting back in a shared ideology, she said.

Because of the eventual drawdown in NATO troop strength in Afghanistan, the ACME labs at Kandahar Airfield, Kandahar Province, and Camp Leatherneck, Helmand Province, were closed and some assets were relocated to BAF's ACME in 2013.

The evidence is collected at the sites of detonation by conventional forces -- explosive ordnance personnel, route clearance personnel -- through personnel working in the Ministry of Interior's National Directorate of Security, and other Afghan partners, Perusse said.

From January 2018 to December 2018, the ACME lab was responsible for:

O 1,145 cases processed based on 36,667 individual exhibits

O 3,402 latent prints uploaded; 69 associations made from unknown to known

O 3,090 DNA profiles uploaded; 59 unique identifications made from unknown to known

O 209 explosive samples, 121 precursors, 167 non-explosives/other, and 40 controlled substances analyzed

O 55 firearms/toolmarks microscopic identifications

Adding credibility to ACME was that it became accredited by the International Organization of Standard in 2015. Both lab managers said they believe that ACME is probably the only deployed Defense Department lab accredited -- besides the FXL-C in Kuwait -- in the forensics field.

The International Organization for Standardization is an international standard-setting body composed of representatives from various national standards organizations comprised of members from 168 countries. It is the world's largest developer of voluntary international standards and facilitates world trade by providing common standards between nations. It was founded in 1947. Tiller and Perusse said this accreditation is quite meaningful, personally and professionally. Interestingly, both lab managers offer extensive deployment experience to the ACME lab.

Tiller has deployed four times for FXD -- three times to Afghanistan and once to Kuwait -- for a total of 26 months. Likewise, Perusse has 28 months of deployment experience too with FXD, with now four deployments in Afghanistan and one to Kuwait. And, because of mission requirements, no rest and relaxation periods -- vacations -- are allowed during their deployments. The reason is because most positions are one-person deep and the mission cannot continue without all sections working collectively, they said. Currently, there are 17 people working at the BAF ACME lab.

FXD's mandatory deployment policy can be viewed as positive and negative depending on a person's particular situation.

As Perusse points out, there are plenty of other places to work that do not require mandatory deployments which require forensic skills such as the Drug Enforcement Administration, the Federal Bureau of Investigation, and Department of Homeland Security to name several.

So those who do work at ACME do so because they want to be. "There is nowhere else in the world where you're going to get a [final] forensic result of the quality that you're going to get from the ACME as quickly as you do," Tiller said, which often brings immediate gratification to one's work.

Whether it's producing a DNA profile or finding a latent print on some material, finding this evidence within two days is a big reason why people at ACME find their work rewarding. "It happens nowhere else," Tiller said, describing it as the "ultimate satisfaction," knowing the evidence produced will ultimately save lives.

As Perusse put it, there is no place like ACME's lab in Afghanistan. "We are in war zone. We are around everything, we get IDFed," she said, referencing the periodic indirect fire of mortar attacks at BAF. She said it is much different type of deployment than at the Kuwait lab where examiners can "have more freedom to include going into the city and shop at the mall."

"There's a reason why we're doing this," Perusse said, of identifying the enemy, which leads to saving lives and helping the NATO coalition. "It's very powerful to be able to see that and be with the people who are going out the field and risking their lives," she said of those who look for and submit items for evidence.

As Tiller redeploys back to her normal duty station in Georgia, she knows ACME will continue in experienced hands with Perusse who will now take over as lab manager for a third time.