An Overview of the Royal Navy’s Light Frigate Programme Following SDSR 2015

| |

|||

| a | |||

Analysis

- UK SDSR 2015 / Light Frigate Programme |

|||

An

Overview of the Royal Navy’s Light Frigate Programme Following

SDSR 2015 |

|||

By Stylianos Kanavakis - Senior Defence Analyst The new UK Strategic Defence and Security Review 2015 set the ground for the future Royal Navy’s force structure. The force structure is outlined in an end-to-end strategic document, as it offers a complete view on UK’s strategic interests, objectives and the means to achieve them. After years of withdrawal from major global policy issues, Britain is looking into covering the lost ground and moving ahead, in an effort to better position itself for the upcoming challenges. |

|||

The first ever image to be released of the Successor submarine. The Vanguard-class SSBNs will be replaced by the Successor-class. Image: BAE Systems |

|||

The strategic interests, as mentioned in the document

are extensive, ranging from peacetime activities and deterrence, to

full-scale warfare against peer enemies, in different locations worldwide.

They include the protection of the population, at home and overseas,

projection of global influence and promotion of British prosperity.

For these reasons, the government has adopted a multifaceted approach,

combining soft and hard power.

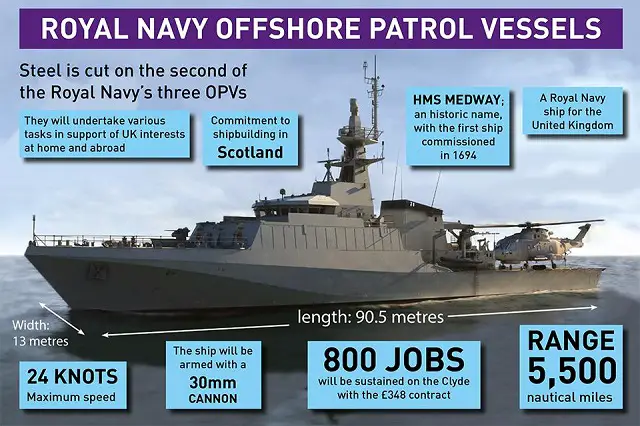

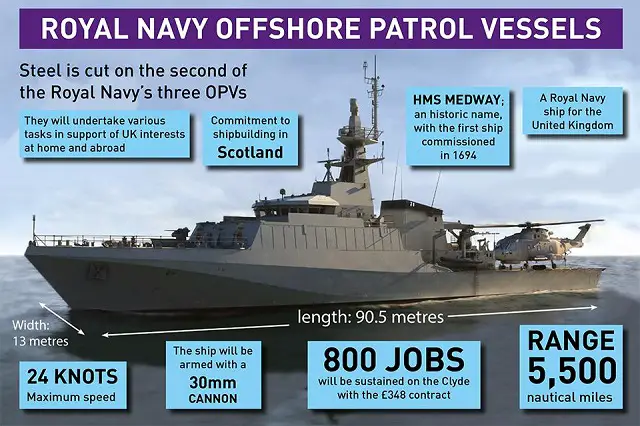

Naval forces, which are the scope of this article, will have an important role as they can undertake a wide range of missions, in the full spectrum between soft and hard power. Furthermore, given the UK’s focus on counter-insurgency operations for the last, almost 15 years, the Royal Navy had been relatively “neglected” when compared to the Army and the Air Force. The new SDSR 2015’s holistic approach on defence and security sets the defence requirements, with the industrial base and the overall need for the UK defence and shipbuilding industry to maintain its global position in manufacturing and innovation. While the SDSR outlines the overall strategy, more details will be provided with the next year’s rollout of the UK Shipbuilding Strategy and the clearer picture on the technical requirements for the Type 26 and lighter frigate. The review solely offers a glimpse of the objectives and the strategy in maritime force structure and industrial strategy. Navy Force Structure According to SDSR 2015 the Royal Navy will be able to provide the necessary forces for the Joint Force 2025 through a pool of: • 4 x SSBN (currently Vanguard-class submarines, which will be replaced by the Successor-class); • 7 x SSN submarines (Astute-class); • 2 x aircraft carriers (Queen Elizabeth-class); • 19 x destroyers and frigates (Type 45 and Type 23 that will be replaced by Type 26 and lighter ones); • 6 x offshore patrol vessels (River-class Batches 1 and 2); • 12 x mine-hunters; • 3 x survey vessels; • 1 x ice patrol ship; • Numbers of landing platforms; helicopters; fleet support vessels; and of course the Royal Marines. What is interesting is the announcement of the reduction in the number of the Type 26 Global Combat Ship frigates that will partially replace the Type 23. Nevertheless, this decision will not deprive the Royal Navy of new capabilities. The fleet of 19 destroyers and frigates will be maintained in the medium-term and increased by 2030 and onwards, with the launch of a concept study for new lighter, general-purpose frigates. |

Italian

Navy's future PPA |

|||

Why build a new class of frigates ?

The decision to build a lighter, more flexible, general-purpose class of frigates bares some resemblance to the French Navy’s FTI (Frégate de TailleIntermédiaire or Medium Sized Frigate), the Italian Navy’s PPA (PattugliatorePolivalante d’ Altura) and the US Navy’s LCS (Littoral Combat Ship) programmes, regarding the need to build a class of ships that would bridge the gap between large (destroyers and frigates) and smaller (OPVs) surface combat units, in an affordable way. Considering that the Type 45 destroyers have a displacement of 8,000 tonnes, the Type 23 4,900 tonnes and the Type 26 7,000 tonnes, the lighter frigate is expected to have a displacement in the range of 3,500-4,500 tonnes. With six Type 45 destroyers already in service and eight Type 26 frigates to be introduced from 2023, the Royal Navy will induct five of the lighter frigates. Such a decision has important implications in the operational capabilities, the shipbuilding industry and its supply-chain and the defence budgets of a country. Below, follows a break-down of these factors, with a focus on the Royal Navy. |

|||

Type 23 Frigate HMS Kent. Picture: Royal Navy |

|||

Operational capabilities

There has hitherto been no clear indication on the technical side of the new lighter frigate. Therefore, it is assumed that the vessels: • Would be capable of fighting inlittoral and blue-waters; • Would have reduced acquisition and operational costs; • Albeit general-purpose it is still open whether they will feature mission-specific packages; • Could feature higher top speed compared to the T45 and T23 to operate safely in stand-alone missions. The light frigate will address the quantity issue, remembering J. Stalin’s quote “quantity has a quality all its own”, but with the addition of affordability. These are the most important factors. Regarding the technical characteristics of the new vessels everything is still under consideration, given that the Royal Navy will need them to operate as part of a task group and in stand-alone operations simultaneously. For example, while undertaking littoral or blue-water combat, peacekeeping, humanitarian, escort, force projection-standing deployments or intelligence missions. In any of the above missions, the anti-submarine (ASW) warfare is probably the most critical component or primary role, mainly due to the proliferation of conventional submarines with AIP propulsion, although air-defence is a capability that should not be neglected as well. Type 45 quantities are inadequate for operations in all theatresrelated to the UK’s foreign policy areas of interest, namely the Atlantic, Arctic Circle, Mediterranean, Red Sea, Persian Gulf, Arabian Sea and Asia. These are environments, which impose completely different or even contradictory requirements. Besides, the Type 26 is destined to replace the Type 23 frigates, which are the backbone of the fleet’s surface combat ships with anti-submarine capabilities and the ones that were able to take over more effectively standing deployment missions. But the expected high cost of the Type 26 has resulted in cutting its numbers, at the expense of the lighter frigate. This complex situation shows that it is not yet apparent what the Royal Navy can afford to have, although requirements seem clear-cut. Under the circumstances, it would be wise to expect some sort of modularity either in the mission packages or the available infrastructure and space on the vessels, to better address the complexity issues in the future, as the big picture will be getting clearer. Lastly, while the Royal Navy has a lot to consider regarding the design parameters of the new vessels, the export markets, especially those of smaller countries,have proved more capable at articulating their needs. This is due to the fact that their strategic interestsdo not impose a large variation in the technical requirements. |

|||

|

|||

UK shipbuilding industry

BAE Systems shipbuilding division has agreed to undergo a restructuring plan in 2013, which included layoffs, restructuring of the Queen Elizabeth-class Aircraft Carrier programme; rationalization of the naval ship business to match future requirements; and undertaking additional shipbuilding work with three more armed OPVs, to fill-up the period until the start of the Type 26 building. In addition to covering the internal needs, the company and of course the UK, aim at the export markets. Unfortunately, the list of countries interested in vessels with the displacement and technical characteristics of the Type 45 destroyer is rather short. Worse, likely customer nations have already building capabilitiesin the designing and buildingof similar ships. The market is thus limited in size and highly competitive in nature. In this business environment BAE Systems has failed to land significant export contracts, with the exception of some OPVs and of major units built by BAE Systems and transferred in the past by the Royal Navy to allied fleets. On the other hand DCNS and Navantia have been more successful with the FREMM and F100 designs. The Type 26 Global Combat Ship has been designed with the exporting opportunities in mind. Nevertheless, the complexity of the design and the cost associated (including the high exchange rates of the British Pound) would still be two points of consideration by many of the potential customers. The light, multi-purpose frigate aspires to succeed in that area. The UK Ministry of Defence will play an active role in promoting the defence industrial and innovation capabilities, with the aim of reassuring prosperity, as mentioned in the SDSR. Defence Secretary, Michael Fallon announced such plans during a speech at DSEi 2015.Most importantly he signaled to the country’s defence industry to design commercially viable products, for export from the start of a programme and not at a later stage when it would be more costly. Moreover these should would also be modular and with an open architecture. In an effort to reduce the development cost, designing of the new vessel is likely to start soon, well before the wind-down of the Type 26’s design from 2016 and onwards, with an eye to foreign competitors who are in track of delivering similar platforms. In other words, there will be an effort to avoid as much as possible the peaks and bottoms in demand. Modularity and open-architecture in the design will benefit the Royal Navy and BAE Systems in configuring the vessels as shipbuilding progresses; with special attention given to avoid frontloading development and focusing on retaining flexibility regarding mission capabilities and cost. |

|||

Type 26 Global Combat Ship program will cost roughly GBP11 billion |

|||

Programme budget

Although the UK Government has decided to dedicate a huge amount of funding for procurement over the next decade, it will still need to take rational and wise decisions, to make the most out of the GBP178 billion. The decision to build eight Type 26 vessels is a firm order, reducing political and financial risk, andallowing the shipyards to plan the procurement of materiel and equipment with a high degree of certainty. In effect, both parties will be able to draw a shipbuilding plan based on their long-term requirements. It is within this framework that the MoD will invest GBP100 million in infrastructure development of the Portsmouth Naval Base that will also support the arrival of the Queen Elizabeth aircraft carriers. According to the latest estimates, the total Type 26 Global Combat Ship program will cost roughly GBP11 billion. It is expected that the cost for the lighter frigate will be significantly lower. The MoD and the industry, making a long-term plan, will suppress overallcosts by streamlining the supply-chain, the personnel training and support requirements. Furthermore, it is expected that there will be a large percentage of commonality between the Type 26 and the light frigate. That would be mostly visible in the systems of the two platforms. Conclusion The SDSR 2015 is an end-to-end strategic approach and as such it integrates the international environment with defence planning, force structure and industrial capabilities in one solid strategy. The Royal Navy will benefit from such a long-term approach, which is vital for the maritime sector, whose capabilities development spans over a large period of time. The decision to reduce the number of Type 26 GCS ships and replace them with more affordable lighter, general-purpose frigates could prove a decision towards the right direction. That is, as long as it manages to provide the Royal Navy with an affordable and capable platform, that will become an export success, thus making the shipbuilding sector sustainable. All these are to be seen whether they will be realized in the near future. |

|||

An Overview of the Royal Navy’s Light Frigate Programme Following SDSR 2015

| |

|||

| a | |||

Analysis

- UK SDSR 2015 / Light Frigate Programme |

|||

An

Overview of the Royal Navy’s Light Frigate Programme Following

SDSR 2015 |

|||

By Stylianos Kanavakis - Senior Defence Analyst The new UK Strategic Defence and Security Review 2015 set the ground for the future Royal Navy’s force structure. The force structure is outlined in an end-to-end strategic document, as it offers a complete view on UK’s strategic interests, objectives and the means to achieve them. After years of withdrawal from major global policy issues, Britain is looking into covering the lost ground and moving ahead, in an effort to better position itself for the upcoming challenges. |

|||

The first ever image to be released of the Successor submarine. The Vanguard-class SSBNs will be replaced by the Successor-class. Image: BAE Systems |

|||

The strategic interests, as mentioned in the document

are extensive, ranging from peacetime activities and deterrence, to

full-scale warfare against peer enemies, in different locations worldwide.

They include the protection of the population, at home and overseas,

projection of global influence and promotion of British prosperity.

For these reasons, the government has adopted a multifaceted approach,

combining soft and hard power.

Naval forces, which are the scope of this article, will have an important role as they can undertake a wide range of missions, in the full spectrum between soft and hard power. Furthermore, given the UK’s focus on counter-insurgency operations for the last, almost 15 years, the Royal Navy had been relatively “neglected” when compared to the Army and the Air Force. The new SDSR 2015’s holistic approach on defence and security sets the defence requirements, with the industrial base and the overall need for the UK defence and shipbuilding industry to maintain its global position in manufacturing and innovation. While the SDSR outlines the overall strategy, more details will be provided with the next year’s rollout of the UK Shipbuilding Strategy and the clearer picture on the technical requirements for the Type 26 and lighter frigate. The review solely offers a glimpse of the objectives and the strategy in maritime force structure and industrial strategy. Navy Force Structure According to SDSR 2015 the Royal Navy will be able to provide the necessary forces for the Joint Force 2025 through a pool of: • 4 x SSBN (currently Vanguard-class submarines, which will be replaced by the Successor-class); • 7 x SSN submarines (Astute-class); • 2 x aircraft carriers (Queen Elizabeth-class); • 19 x destroyers and frigates (Type 45 and Type 23 that will be replaced by Type 26 and lighter ones); • 6 x offshore patrol vessels (River-class Batches 1 and 2); • 12 x mine-hunters; • 3 x survey vessels; • 1 x ice patrol ship; • Numbers of landing platforms; helicopters; fleet support vessels; and of course the Royal Marines. What is interesting is the announcement of the reduction in the number of the Type 26 Global Combat Ship frigates that will partially replace the Type 23. Nevertheless, this decision will not deprive the Royal Navy of new capabilities. The fleet of 19 destroyers and frigates will be maintained in the medium-term and increased by 2030 and onwards, with the launch of a concept study for new lighter, general-purpose frigates. |

Italian

Navy's future PPA |

|||

Why build a new class of frigates ?

The decision to build a lighter, more flexible, general-purpose class of frigates bares some resemblance to the French Navy’s FTI (Frégate de TailleIntermédiaire or Medium Sized Frigate), the Italian Navy’s PPA (PattugliatorePolivalante d’ Altura) and the US Navy’s LCS (Littoral Combat Ship) programmes, regarding the need to build a class of ships that would bridge the gap between large (destroyers and frigates) and smaller (OPVs) surface combat units, in an affordable way. Considering that the Type 45 destroyers have a displacement of 8,000 tonnes, the Type 23 4,900 tonnes and the Type 26 7,000 tonnes, the lighter frigate is expected to have a displacement in the range of 3,500-4,500 tonnes. With six Type 45 destroyers already in service and eight Type 26 frigates to be introduced from 2023, the Royal Navy will induct five of the lighter frigates. Such a decision has important implications in the operational capabilities, the shipbuilding industry and its supply-chain and the defence budgets of a country. Below, follows a break-down of these factors, with a focus on the Royal Navy. |

|||

Type 23 Frigate HMS Kent. Picture: Royal Navy |

|||

Operational capabilities

There has hitherto been no clear indication on the technical side of the new lighter frigate. Therefore, it is assumed that the vessels: • Would be capable of fighting inlittoral and blue-waters; • Would have reduced acquisition and operational costs; • Albeit general-purpose it is still open whether they will feature mission-specific packages; • Could feature higher top speed compared to the T45 and T23 to operate safely in stand-alone missions. The light frigate will address the quantity issue, remembering J. Stalin’s quote “quantity has a quality all its own”, but with the addition of affordability. These are the most important factors. Regarding the technical characteristics of the new vessels everything is still under consideration, given that the Royal Navy will need them to operate as part of a task group and in stand-alone operations simultaneously. For example, while undertaking littoral or blue-water combat, peacekeeping, humanitarian, escort, force projection-standing deployments or intelligence missions. In any of the above missions, the anti-submarine (ASW) warfare is probably the most critical component or primary role, mainly due to the proliferation of conventional submarines with AIP propulsion, although air-defence is a capability that should not be neglected as well. Type 45 quantities are inadequate for operations in all theatresrelated to the UK’s foreign policy areas of interest, namely the Atlantic, Arctic Circle, Mediterranean, Red Sea, Persian Gulf, Arabian Sea and Asia. These are environments, which impose completely different or even contradictory requirements. Besides, the Type 26 is destined to replace the Type 23 frigates, which are the backbone of the fleet’s surface combat ships with anti-submarine capabilities and the ones that were able to take over more effectively standing deployment missions. But the expected high cost of the Type 26 has resulted in cutting its numbers, at the expense of the lighter frigate. This complex situation shows that it is not yet apparent what the Royal Navy can afford to have, although requirements seem clear-cut. Under the circumstances, it would be wise to expect some sort of modularity either in the mission packages or the available infrastructure and space on the vessels, to better address the complexity issues in the future, as the big picture will be getting clearer. Lastly, while the Royal Navy has a lot to consider regarding the design parameters of the new vessels, the export markets, especially those of smaller countries,have proved more capable at articulating their needs. This is due to the fact that their strategic interestsdo not impose a large variation in the technical requirements. |

|||

|

|||

UK shipbuilding industry

BAE Systems shipbuilding division has agreed to undergo a restructuring plan in 2013, which included layoffs, restructuring of the Queen Elizabeth-class Aircraft Carrier programme; rationalization of the naval ship business to match future requirements; and undertaking additional shipbuilding work with three more armed OPVs, to fill-up the period until the start of the Type 26 building. In addition to covering the internal needs, the company and of course the UK, aim at the export markets. Unfortunately, the list of countries interested in vessels with the displacement and technical characteristics of the Type 45 destroyer is rather short. Worse, likely customer nations have already building capabilitiesin the designing and buildingof similar ships. The market is thus limited in size and highly competitive in nature. In this business environment BAE Systems has failed to land significant export contracts, with the exception of some OPVs and of major units built by BAE Systems and transferred in the past by the Royal Navy to allied fleets. On the other hand DCNS and Navantia have been more successful with the FREMM and F100 designs. The Type 26 Global Combat Ship has been designed with the exporting opportunities in mind. Nevertheless, the complexity of the design and the cost associated (including the high exchange rates of the British Pound) would still be two points of consideration by many of the potential customers. The light, multi-purpose frigate aspires to succeed in that area. The UK Ministry of Defence will play an active role in promoting the defence industrial and innovation capabilities, with the aim of reassuring prosperity, as mentioned in the SDSR. Defence Secretary, Michael Fallon announced such plans during a speech at DSEi 2015.Most importantly he signaled to the country’s defence industry to design commercially viable products, for export from the start of a programme and not at a later stage when it would be more costly. Moreover these should would also be modular and with an open architecture. In an effort to reduce the development cost, designing of the new vessel is likely to start soon, well before the wind-down of the Type 26’s design from 2016 and onwards, with an eye to foreign competitors who are in track of delivering similar platforms. In other words, there will be an effort to avoid as much as possible the peaks and bottoms in demand. Modularity and open-architecture in the design will benefit the Royal Navy and BAE Systems in configuring the vessels as shipbuilding progresses; with special attention given to avoid frontloading development and focusing on retaining flexibility regarding mission capabilities and cost. |

|||

Type 26 Global Combat Ship program will cost roughly GBP11 billion |

|||

Programme budget

Although the UK Government has decided to dedicate a huge amount of funding for procurement over the next decade, it will still need to take rational and wise decisions, to make the most out of the GBP178 billion. The decision to build eight Type 26 vessels is a firm order, reducing political and financial risk, andallowing the shipyards to plan the procurement of materiel and equipment with a high degree of certainty. In effect, both parties will be able to draw a shipbuilding plan based on their long-term requirements. It is within this framework that the MoD will invest GBP100 million in infrastructure development of the Portsmouth Naval Base that will also support the arrival of the Queen Elizabeth aircraft carriers. According to the latest estimates, the total Type 26 Global Combat Ship program will cost roughly GBP11 billion. It is expected that the cost for the lighter frigate will be significantly lower. The MoD and the industry, making a long-term plan, will suppress overallcosts by streamlining the supply-chain, the personnel training and support requirements. Furthermore, it is expected that there will be a large percentage of commonality between the Type 26 and the light frigate. That would be mostly visible in the systems of the two platforms. Conclusion The SDSR 2015 is an end-to-end strategic approach and as such it integrates the international environment with defence planning, force structure and industrial capabilities in one solid strategy. The Royal Navy will benefit from such a long-term approach, which is vital for the maritime sector, whose capabilities development spans over a large period of time. The decision to reduce the number of Type 26 GCS ships and replace them with more affordable lighter, general-purpose frigates could prove a decision towards the right direction. That is, as long as it manages to provide the Royal Navy with an affordable and capable platform, that will become an export success, thus making the shipbuilding sector sustainable. All these are to be seen whether they will be realized in the near future. |

|||