Breaking News

Focus | Is the US right to see an intercontinental ballistic missile threat in Iran’s satellite launch program?.

In the 2025 USSTRATCOM posture statement, Commander Gen. Anthony Cotton highlighted Iran’s growing work on space-launch rockets, particularly the two-stage Simorgh space launch vehicle (SLV), and warned that these efforts “likely shorten the timeline to produce an ICBM [intercontinental ballistic missile] due to the similarities in technology.” The Simorgh rocket, for example, uses propulsion systems comparable to those needed for an ICBM and could theoretically deliver a payload over 2,400 miles (≈3,860 km) if weaponized. As Iran advances its space program, which is ostensibly aimed at placing satellites in orbit, some US officials are increasingly concerned that Tehran is perfecting long-range missile capabilities under the cover of peaceful satellite launches.

Follow Army Recognition on Google News at this link

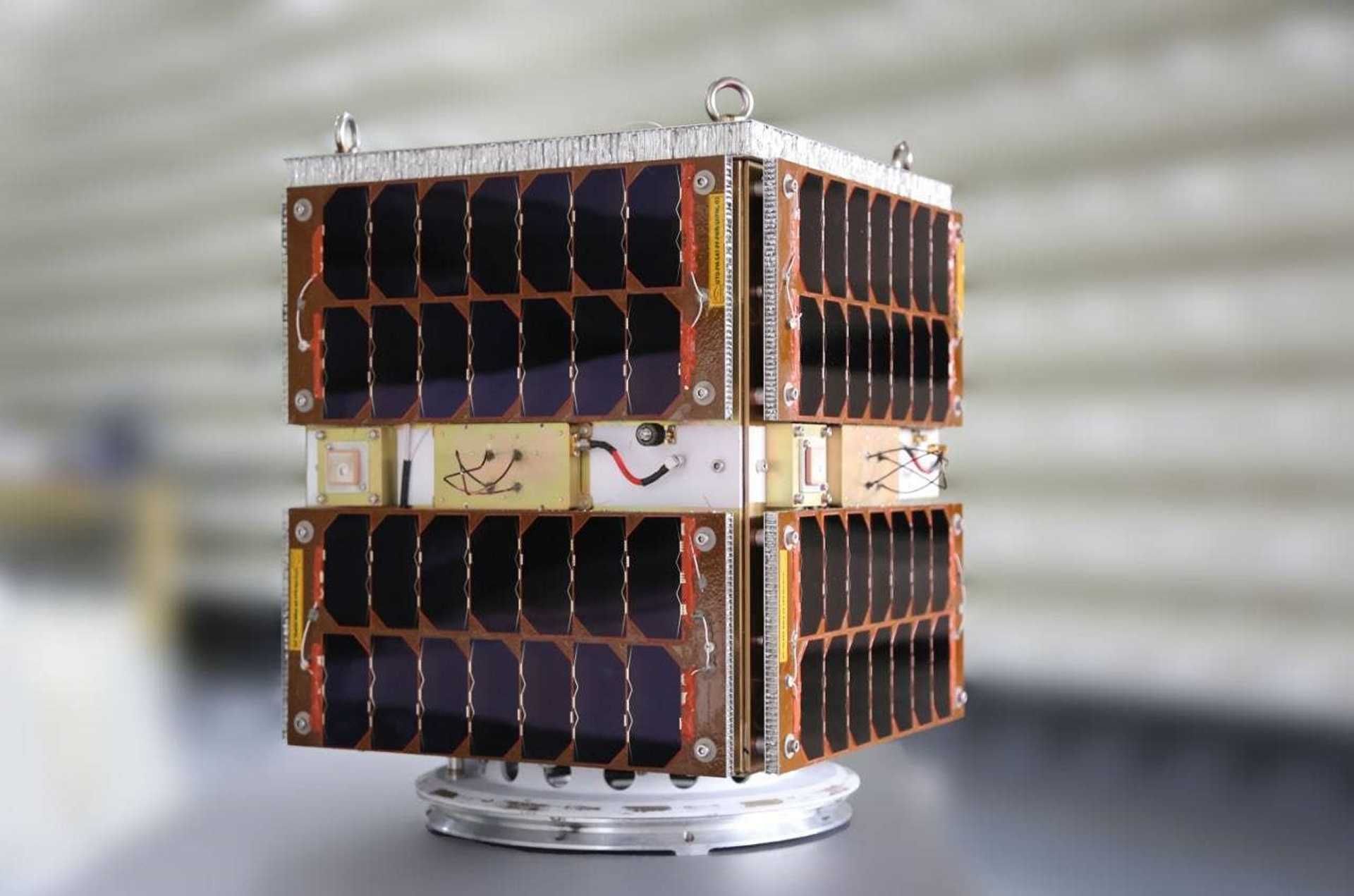

Iran’s space rockets are often derived from modified ballistic missiles. For example, the Safir used the Shahab’s engine for its first stage and a smaller second stage to place payloads into orbit, while its successor, the Simorgh, is already able of carrying heavier payloads to higher altitudes. (Picture source: Iranian MoD)

Iran’s quest for space capability has yielded some notable successes over the past decade. In February 2009, Iran became the ninth country to launch an indigenous satellite into orbit when a two-stage Safir rocket carried the Omid satellite into low-Earth orbit. That achievement marked a milestone for Iran’s civilian space agency and demonstrated basic proficiency in building multi-stage rockets.

The Safir (“Ambassador”) space launch vehicle (SLV), which was based on an extended version of Iran’s Shahab-3 ballistic missile, completed a handful of successful launches between 2009 and 2015, orbiting small satellites (weighing under 50 kg) into low orbit. Building on this foundation, Iran introduced the larger Simorgh (“Phoenix”) space launch vehicle in 2010, aiming to lift heavier satellites (~250 kg class) and reach higher orbits. The Simorgh is a roughly 27-meter-tall, liquid-fueled, two-stage rocket, reportedly capable of placing a satellite into a 500 km altitude orbit.

After years of development delays, the first Simorgh launch attempt occurred in April 2016, followed by additional tests in 2017 and 2019. Iran’s regular armed forces were not the only ones pursuing space: starting in 2020, the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) began a parallel program using a solid-fuel SLV called Qased. In April 2020, the IRGC surprised many by successfully lofting the Noor-1 military satellite into an orbit about 425 km high. This marked Iran’s first military satellite and the first successful launch by the IRGC’s aerospace wing. The IRGC followed up with Noor-2 in March 2022 and Noor-3 in September 2023, both reaching orbit via Qased rockets. These accomplishments, three small imaging satellites now in orbit, indicate that Iran’s space program, though limited in scope, is maturing. Each launch, whether by the civilian agency or the IRGC, contributes to Iran’s growing expertise in staging, propulsion, and launch operations.

The technical commonalities between space launch rockets and long-range ballistic missiles lie at the heart of international concern. U.S. intelligence analysts assess that many components of the Simorgh SLV could be directly repurposed for building long-range missiles. Both SLVs and ICBMs require powerful multi-stage engines, guidance and control systems to maintain stable trajectories, and lightweight airframes to maximize range.

Indeed, Iran’s Safir rocket was a modified variant of its Shahab-3 medium-range missile, using the Shahab’s engine for the first stage and a smaller second stage to boost payloads to orbit. The Simorgh is believed to cluster multiple Shahab-3-derived engines, effectively scaling up from MRBM technology to a larger booster. Although its existence remains unconfirmed, the Project Koussar, also known as Kowsar, has been mentioned in Western publications as part of broader concerns over Iran’s long-range missile ambitions, including the alleged Shahab-5 and Shahab-6. This project is reportedly an Iranian missile program linked to efforts to develop an IRBM or ICBM, using Russian RD-216 engine technology, with a potential range of 4,000 to 5,000 km.

The Simorgh is a roughly 27-meter-tall, liquid-fueled, two-stage rocket, reportedly capable of placing a satellite into a 500 km altitude orbit. (Picture source: Iranian MoD)

“The technology used on Iran’s satellite launchers is virtually identical to that on ballistic missiles designed to deliver nuclear warheads,” warned U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo in 2019. The only major difference between an SLV and an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) is the payload: one carries a satellite with no re-entry, while the other carries a re-entry vehicle with a warhead. Mastering one brings Iran closer to mastering the other.

The U.S. Defense Intelligence Agency has similarly reported that Iran’s development of more powerful space launch boosters could provide a base from which an ICBM could be built “if configured for that purpose.” According to DIA Director Lt. Gen. Robert Ashley, while Iran does not currently possess an ICBM, the Simorgh and similar launchers could serve as stepping stones. “They could [use] that space launch vehicle and start working it toward an ICBM capability,” he told Congress, though he assessed that such a step remained years away.

In short, every Iranian satellite launch vehicle test can also be viewed as a partial test of an ICBM in disguise by the United States. Western experts point to Iran’s use of technologies such as storable liquid propellants (in the Simorgh), which allow missiles to be fueled in advance, and solid propellants (in the IRGC’s Qased and the new Zuljanah SLV) as evidence that Iran is systematically acquiring know-how applicable to long-range missiles. Additionally, experience gained in stage separation, space guidance, and even warhead shroud design for SLVs all translates to ICBM development skills.

Iran’s SLV program has had its share of setbacks, underlining both the difficulty of the technology and the opportunities for iterative learning. The first Safir launch attempt in August 2008 failed to reach orbit, but Iran quickly corrected course and succeeded on the next try in 2009.

The larger Simorgh rocket’s debut in 2016 was reportedly only a sub-orbital test, and its 2017 launch ended in failure during the second-stage burn. U.S. tracking confirmed no satellite was deployed. Another Simorgh launch in January 2019, carrying a satellite named Payam, also fell short of orbit, Iranian officials stated that the rocket failed to reach the required speed in the final stage.

The Trump administration condemned these launches as provocative missile tests in disguise and imposed sanctions on Iran’s space entities. Despite three consecutive Simorgh failures, Iran persisted. In February 2020, a Simorgh variant (sometimes referred to as the “Simorgh/Zafar”) was launched with a new satellite; that too failed to achieve orbit, though Iranian media claimed partial success.

As of 2023, outside analysts assess that the Simorgh SLV has yet to reliably orbit a satellite, indicating ongoing technical hurdles. In contrast, the IRGC’s Qased solid-fuel rocket has succeeded in 3 out of 3 attempts, albeit with lighter payloads (~50 kg). The IRGC’s success suggests that Iran’s military may have leapfrogged some of the civilian program’s challenges by adopting a hybrid design (solid first stage, liquid second) and possibly drawing on foreign expertise in solid-fuel technology.

The only major difference between a space launch vehicle (SLV) and an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) is the payload: one carries a satellite with no re-entry, while the other carries a re-entry vehicle with a warhead. (Picture source: IRNA)

Each failure and success provides Iran with valuable data, engine performance, stage separation dynamics, telemetry, and flight control feedback, that informs improved designs. Iranian scientists have demonstrated persistence and incremental progress, a pattern seen in other spacefaring nations. Western space trackers continue to monitor activity at Iran’s Semnan launch complex via satellite imagery, often detecting preparations for launches weeks in advance. Such visibility underscores the relative transparency of missile development pursued via space launch programs.

Iran’s satellite program has become a focal point of international diplomatic disputes due to its dual-use nature. The United States and European powers argue that Iran’s SLV tests contravene the spirit of UN Security Council Resolution 2231, which in 2015 “called upon” Iran to refrain from activities related to ballistic missiles capable of delivering nuclear weapons. Although this language fell short of an outright ban (and officially expired in 2023), Western officials argue that launches like the Simorgh are essentially veiled missile tests.

They note that no civilian need justifies Iran’s development of such large rockets at this stage. Iran’s satellites to date have been militarily useful (for reconnaissance), but not critical enough to explain the investment, unless the program serves a strategic weapons purpose. For this reason, the U.S. has frequently sanctioned Iran’s space launch organizations and any foreign partners assisting them.

Iran, however, strongly rejects these accusations. Iranian leaders assert that all space activities are legitimate under international law, pointing out that no provision of the JCPOA or other agreements explicitly prohibits satellite launches. Tehran insists on its right to peaceful space use and frequently cites India, Israel, and North Korea as other nations with SLVs. Iranian officials highlight achievements like the Noor satellites as proof of progress and national pride, while denying any pursuit of ICBMs.

Still, the inherent dual-use potential is hard to ignore. A European diplomat noted, “there is no meaningful difference between an ICBM and a space launcher, only what you stick on top of it.” This skepticism is echoed by Iran’s own statements. For example, IRGC Aerospace Force Commander Brig. Gen. Amir Ali Hajizadeh has said that if Iran ever decided to build missiles with over 2,000 km range, it could do so, suggesting latent capacity.

As of early 2025, Iran has not flight-tested any missile that qualifies as an ICBM (generally defined as having a range over 5,500 km). Its longest-range confirmed missiles remain near the 2,000 km threshold. However, advances in Iran’s space program suggest that the gap to an ICBM is primarily a matter of political decision-making and further testing, not technical barriers.

If Iran were to integrate the technologies demonstrated in the Simorgh or the solid-fueled Zuljanah SLV into a weapon system, it could potentially develop an intermediate- or intercontinental-range missile. Western intelligence estimates vary, but many concur with the DIA’s assessment that Iran remains several years away from deploying an ICBM, and that there is currently no evidence Iran is constructing the complex reentry vehicles and guidance systems needed for an accurate warhead.

In the meantime, Iran is expected to continue launching satellites for civil or military purposes, reconnaissance, communications, and scientific research. Each launch will be watched closely. The 2025 USSTRATCOM posture statement explicitly noted that the Simorgh program “shortens the timeline” for an ICBM, reflecting the strategic concern in the U.S. defense community.

Future negotiations with Iran, on renewing the nuclear deal or crafting a new arrangement, may seek to include constraints on long-range missile development, including SLVs. For now, in the absence of a binding agreement, Iran faces few legal obstacles in continuing its space activities. The risk remains that Tehran’s satellite program could seamlessly transition into a long-range missile capability. As one non-proliferation expert put it, Iran’s satellite launch vehicles are essentially “ICBMs in all but name”, and the world will be watching to see whether Tehran decides to rebrand them as such.